John Sewell: How We Changed Toronto – The inside story of twelve creative, tumultuous years in civic life, 1969-1980.

Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4594-0940-8 (BOUND), 343 pages plus index.

Reviewed by Max Allen, September 2015

Like Rob Ford, John Sewell was once mayor of Toronto. The similarity ends there.

Or does it? Both were one-term mayors who had been councillors first. And they were both elected on far-reaching platforms, at a time when Toronto politics was front page news.

I was a constant presence in the media, with a daily stream of stories about what I was doing and saying, but there was often an unpleasant edge to the coverage with an underlying implication that I was deliberately provocative. [p.314]

One difference between Ford and Sewell is that the legacy of Sewell and his fellow reformers can still be seen today, in the physical city of Toronto. Sewell got things done. This book tells how.

We began by attempting to undo the past. It was almost unheard of for City Council to even think of undoing past decisions, but we wanted to repeal the decisions which we thought were wrong. We assumed that one function of government was to make change, and for us that meant changing bad decisions. [p.91]

Sewell describes who that “we” involved. It was not, as you might suppose, mostly professional politicians. The book starts with a seven-page Cast of Characters – sixty of them, each with a mini-biography – followed by 328 pages of drama.

John Sewell says the years between 1968 and 1980 were “tumultuous.” That’s an understatement. He illustrates the turmoil with one detailed story after another, over 400 by my count, plus 35 photos, drawings and diagrams, maps and a newspaper cartoon, and a very useful index. All in a book skillfully organized with the help of his editor, Doris Cowan.

Sewell spent most of his early life unaware of the city around him. Then, while he was an articling law student, he was taken by friends to some neighbourhood meetings about “urban renewal,” and it changed his life.

I learned two very powerful lessons. First, City Hall thought the way to improve the city was to tear it down and start over. [They] had no interest in listening to what local people thought would be a better way to improve their neighbourhood. By late 1968, I had learned my second lesson: it made no sense to keep fighting the politicians at city hall and trying to get them to change their minds about how to improve the city. Instead, I should try to displace one of them by running as a candidate for alderman in the December 1969 election. [pp.27-28]

It was a time when the Trefann Court area on Queen Street between Parliament and River Streets was threatened with demolition; so was Don Mount; so was Cabbagetown (today one of Toronto’s most desirable neighbourhoods) which was going to be levelled for apartment towers and a shopping mall. Plans were afoot to tear down Old City Hall. The Spadina Expressway was scheduled to cut Toronto in half.

Into this came John Sewell, riding his bike.

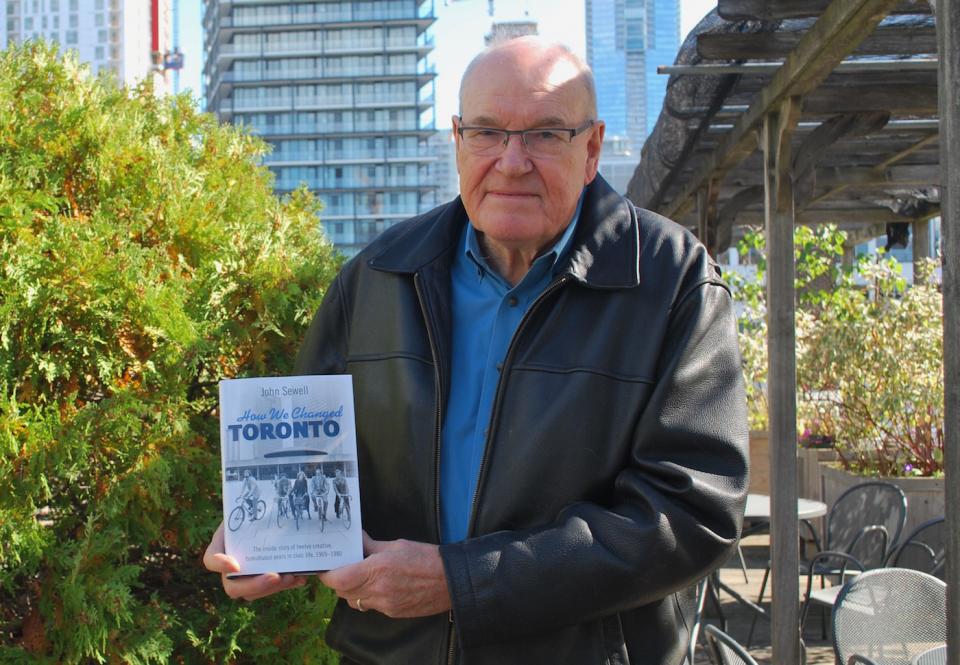

The book’s cover shows Sewell and four of his colleagues on their bicycles in front of City Hall, on Bike to Work Day [day!] in 1980. Transportation was in the back of the minds of the reformers during Sewell’s time, but it wasn’t their primary concern, as it probably would be today. Building a livable city with services for everybody, rich and poor alike, was the aim. It was a conservative agenda, in the old-fashioned sense, although it seemed to be anything but. It was an agenda of ideas, not merely of numbers – unlike today where the height of buildings seems to be the main concern, or at best a handy cover for issues that are far more complicated and intractable and more costly to address.

As a result of the 1969 election, Sewell and his fellow reformers were outnumbered on City Council, but they set to work talking and persuading.

As reform politicians we knew what we wanted to do to protect neighbourhoods, and we quickly moved to set up planning processes engaging residents to create new land-use plans for the places where they lived. By the end of 1973, there were more than thirty working committees devising such plans for as many neighbourhoods. [p.141.]

A useful ally on many civic issues was David Crombie, also newly elected to city council, who became mayor in 1972. My memory of the time was that Sewell and Crombie were great friends, always on the same team. Sewell tells a different story. The details of their many disagreements, and their continuing friendship and civil cooperation, is a lesson of how politics can work. When Crombie’s term as mayor was over and he won a Conservative seat in Ottawa in 1978, Sewell ran in Toronto to succeed him as mayor, running partly against Crombie’s record.

Sewell was a whirlwind. He and his reform colleagues were everywhere. In the late 1960s the city-appointed library board decided to build large district libraries and to close local, neighbourhood branches. One, Northern District Library, was built. But the overall big-box plan was halted in 1974 after the reformers appointed publisher Jim Lorimer to the library board (he later became chairman). In the next six years, fifteen local branch libraries were renovated and often expanded, with input from local residents. Today, Toronto’s library system is the most-used library system in the world.

A friend of mine, when I was telling her about this book, said she didn’t care about what happened in Toronto forty years ago, any more than she cared how other cities managed various urban projects. She said such comparisons weren’t helpful. For example, she reminded me that New York has taxing power but Toronto doesn’t, so of course New York can do spectacular things. And the relationship between Toronto and the province of Ontario is much different now than it used to be – not to mention that the amalgamated city is a larger world than it was when the City of Toronto meant, essentially, downtown. So there could be no useful lessons. But there are. Many of them have to do with procedures and styles of argument.

Most of us had a sense that it was our responsibility to bring our best ideas to the table and debate those ideas in a forthright manner. Yes, there was a lot of criticism back and forth (I was constantly being criticized for suggesting a course of action out of the blue, without warning), but it was a very open environment as those elected to office looked for new approaches. Ideas were never rejected because of who suggested them. [p.107]

But there were also terrible ideas and procedures in play, especially when it came to “building” Toronto, where senior city staff and the developers, according to Sewell, “shared the same values and had no trouble speaking the same language and pursuing the same goals.” [p.53]. One notorious tactic used by developers in pursuing what Sewell calls “the high-rise onslaught” was blockbusting.

Meridian (and other developers) assembled properties by a process we called blockbusting. The company would buy a house, then rent it out to a middleman who turned it into a rooming house. Management was loose and repairs were rarely made; since those who lived there were mostly single men with few resources, they rarely complained. Middlemen moved tenants every three or four months just to keep them insecure. When a middleman-controlled house became enough of a problem to a nearby homeowner, the owner phoned Meridian to complain and Meridian would then make them an offer to buy (their house). In that way, the company picked up another property. Some rooming houses experienced emergencies such as fires, which gave the area a strong sense of instability and even danger. … When houses became really derelict and left empty and without electricity or water, they became a place for the homeless to lodge (which explains some of the fires, as the homeless built fires to keep warm). The houses were demolished, leaving a hole filled with rubble on the street. In a few cases where an owner appeared reluctant to sell, Meridian would demolish the abutting property, and if the two houses shared a common wall (which was often the case with the many row houses in the area) the hold-out owner felt especially threatened. This blockbusting technique was a perfect recipe for Meridian to buy properties cheaply and quickly. [p.49]

What to do? In the summer of 1970 Meridian gave notice to tenants to vacate twenty-five houses that the company owned. A tentative Tenant’s Union was formed which offered to rent the houses from Meridian as a group. The president of Meridian refused but said he’d rent them to Sewell! Sewell decided to take him up on the offer, arranged bank financing, signed the lease, and union members worked to fix up the houses. The neighbourhood stabilized. Alarmed, Meridian cancelled the deal and ordered the tenants out. The tenants had nowhere to go, so they stayed. Meridian sued Sewell for, eventually, almost half a million dollars. The sheriff arrived with a hundred or so police officers to evict the tenants.

Some had chained themselves to radiators so they could not be removed. … I was pushed aside. The police gained entry to the houses and began to lead people out in handcuffs. The scene was mayhem, with people yelling, and police officers making a show of force. Within an hour or two the police had cut the chains of those affixed to the radiators, and cleared the houses of people. Meridian immediately sent in workmen to begin demolition. It was extraordinarily deflating to see that the repairs we had made to the houses were being taken apart, and houses were becoming piles of rubble. Over the coming months, more houses on Bleecker and Ontario Streets were demolished. Within a year, Meridian had managed to demolish many of the houses we had tried to protect. [pp.55-56]

Meridian’s lawsuit again Sewell was finally heard in late 1976. Sewell won. A great many houses had been lost, but the stampede of high-rise buildings from St. Jamestown to the surrounding neighbourhoods was reined in by the unremitting efforts of the reformers.

Another significant result of the reformers’ attempts to bring some socially-responsible order to downtown development was Toronto’s legendary 45-foot Holding Bylaw of 1973, which put the brakes on high-rise development by temporarily limiting new buildings to four or five storeys – until the bylaw was overturned by the Ontario Municipal Board. It was followed by the Central Area Plan, which reinforced heritage preservation and brought some discipline to cowboy development.

In January 1976, City Council spent a final week on the Central Area Plan. Debate is not a strong enough word to describe what happened: it was a bitter and rancorous fight. We were all at the end of our tethers after years of approving or rejecting exemptions to the Holding Bylaws and countless debates about the large and small points that the plan made. The plan was approved by City Council by a vote of fourteen to seven. … The Central Area Plan was then sent off to the Ontario Municipal Board for hearings. … Many land owners, represented by over thirty law firms, were in opposition. Their planners and architects testified that the proposed plan was not feasible and would destroy the downtown. The Board hearing occupied most of 1977 and 1978 – an enormously expensive exercise for the city and for the development industry, establishing a pattern that flowered in later years where more money was spent on lawyers at the Ontario Municipal Board than was spent by planners creating the planning documents in the first place. [pp.160-161]

On a happier note, Sewell describes – at length and in useful detail – how he and his colleagues managed to put together the attractive St. Lawrence neighbourhood on a large swath of unpromising and mostly unused downtown land next to the railway corridor. A working committee was formed (one of Sewell’s favourite tactics; Crombie opposed it) to help the professional planners make the right choices, including having a third of the residential units for low-income families as an integral part of the overall development.

While there were many tense moments between staff and the committee as we got the first buildings under way, I believe it was a healthy tension, and it meant that the elected representatives as well as senior staff had to perform at a very high level. [p.127]

We’re seeing a contemporary replay of the patience and persuasion necessary to bring about a project of this size in the work of Waterfront Toronto, the multi-government agency that to date has organized a whole new section of Toronto in what’s called the West Donlands, by salvaging land and reengineering the mouth of the Don River, adding parks, and partnering with private development companies and their architects to build an Athletes’ Village for the Pan American Games which will turn into private residences for about 10,000 people.

During Sewell’s tenure on council and as mayor, Toronto consisted largely of a downtown commercial area surrounded at various distances by residential areas. People seldom lived in areas where they worked. Industrial operations of all kinds were moving, or had already moved, to the suburbs. Downtown offices were empty at night, and the streets were mostly deserted. Could this be changed?

A large number of new residents could add to the desired twenty-four-hour vitality of the core. People who lived downtown could walk to work. How many people would be living downtown in the next twenty or thirty years? What kinds of densities were needed to encourage developers to build new housing downtown or close to downtown? Would developers actually do something as unthinkable as build housing in the downtown of a city, something that hadn’t happened for seventy or eighty years? [p.149]

Sewell and his colleagues set out to answer these questions. The ensuing population explosion in downtown Toronto has brought many people closer to work. But not enough. And the public and private transportation problem today is worse than the reformers ever imagined. It seems to me that the current impasse at City Council over what to do about this could use John Sewell’s sharp mind and powers of persuasion. After all, Chapter 13 of How We Changed Toronto is called “Acting Creatively to Solve Problems.”

How were the houses on the islands in Toronto Harbour saved from demolition? How was the island airport shaped? How was the Harbourfront/Harbour Square neighbourhood born? How did gay rights became a political issue? How did police reform come about (sort of)?

Why wasn’t Sewell re-elected?

This book, as the subtitle promises, tells the inside stories.

Max Allen has been a CBC Radio producer since 1971, founded the Textile Museum of Canada, edited Ideas That Matter–The Worlds of Jane Jacobs and Eb Zeidler’s Buildings Cities Life, and is the VP for Planning and Development of the Grange Community Association. He has lived in Toronto since 1967.